Hard-Rock Mining in California: A Highway 49 Driving Tour to Jackson

This blog follows my VoiceMap audio driving tour Hard-Rock Mining in California: A Highway 49 Driving Tour to Jackson. As you drive along some of California's most peaceful backroads, we will share with you the history of the California Gold Rush. We will visit the towns of Placerville, Fiddletown, Sutter Creek and Jackson as well as visit a number of hard-rock mines, or at least what remains of them. To bring this story to life we will weave in excerpts from miners' diaries.

You may download a souvenir brochure for this tour here. We have also created a companion brochure, Hiking and Walking Tours of the Gold Country. Download that here if you are interested.

The audio driving tour, it is available at VoiceMap and listed under Amador County. To use VoiceMap, you will need to download the VoiceMap app from the Apple Store or Google Play. The app is free, this audio driving tour, which is one of four that takes you along the Mother Lode from Auburn to Jamestown, currently sells for $11.99. You may read the first blog in this series at California's Gold Rush: A Highway 49 Driving Tour from Auburn to Placerville.

On our drive from Placerville to Jackson we will travel through parts of California's historic Mother Lode, one of the state's best-known gold mining districts, and the picturesque Shenandoah Valley. Our journey starts in Placerville and follows lush vineyard-covered backroads to Jackson. You'll learn about the hard-rock mining era of the California Gold Rush which began in the 1850s, shortly after the area's placer mines began to run dry. You'll drive through the California Gold Rush towns of Fiddletown, Amador City, Sutter Creek and Jackson. You'll also visit the Shenandoah Valley and learn how wine making, which also started here in the 1850s, created liquid gold for some of the early pioneers.

Along the way you can look forward to:

• Learning about different types of mining such as placer, hard-rock, and hydraulic

• Hearing stories about actual mining life, plucked from the pages of a gold miner’s diary

• Finding out about the challenges of traveling to California by land or sea in 1848

• Visiting a water-powered foundry and machine shop

• Taking in the beauty of the peaceful, untouched backroads of California

• Wandering through the old western-style gold rush towns and perusing their antique stores with the help of our companion brochure

This 53-mile driving tour may be completed in about 2 1/2 hours without any stops. On the other hand, this is your adventure. You may stop where you want when you want and for as long as you want. It’s up to you. Or just use this guide to create your own trip. Happy Adventures and enjoy the tour!

+++

This driving tour begins in the parking lot next to the El Dorado Savings Bank

near the intersection of Main Street and Sacramento Street in Historic Old Town

Placerville.

If you are interested in taking a self-guided walking tour of Old Town

Placerville check out our detailed map of the town in our Companion Brochure.

Before we get started on our driving tour here is a bit of background on the City of Placerville.

In late 1848, just 10 months after gold had been discovered eight miles away in Coloma, thousands of miners descended on this location. The town was originally called Dry Diggins, after the dry diggings method used to extract gold from the dirt of a seasonal creek bed. A year later Dry Diggins would receive a new name, Hangtown.

During the winter of 1849 five immigrants were caught and accused of

robbery. Three of them, two Frenchmen

and one Chilean, were singled out as wanted fugitives. With no sheriff or official rule of law, the

trial which was conducted by an angry mob was swift. It ended with all three being hung from an

oak tree on Main Street. At that

time, this was not out of the ordinary.

In fact, justice in mining camps was often referred to as ‘Judge Lynch’ or

judge by lynching. Newspapers picked up

the story and gave the town the nickname Hangtown.

When California became a state in 1850, the State Legislature gave the town the name Placerville after the placer mining method, a way of panning for gold in local stream beds.

For the next four years the names Hangtown and Placerville were used interchangeably. In 1854, then the third most populated town in California, Hangtown was officially incorporated as Placerville.

While other early mining towns came and went, Placerville continued to grow and prosper long after the placers ran dry of gold. What made Placerville such a highly desirable place to live? The answer, location, location, location.

Positioned at the nexus of three overland trails immigrants traveled through Placerville whether they came from Coloma in the north, Sacramento in the west or the Sierra foothills to the east. Those early overland trails have now become two major California highways, 49 and 50 respectively.

Thomas Hittell described Placerville this way in his 1870 book, History Of California, “The town, as it grew up, after tents gave way to cabins and houses, became a straggling collection of buildings along a ravine. It grew rapidly for a few years and was one of the briskest places in the mountains. It became a great place of resort for all the miners who would flock in from every direction to get or dispatch a letter, to meet friends, hear news, lay in new stocks of supplies, or see the excitement of the bar-room and gaming table.”

Prior to the gold rush, this area was sacred to the Northern Miwok native people as a burial ground.

Paolo Sioli wrote this about the Miwok in his 1883 book, Souvenir of El Dorado County, “For hundreds of miles around the dead were transported on litters to this sacred spot, where it was supposed that the spirits of the departed, in the flames of the pine, took their departure to the happy hunting ground beyond the sky.”

In 1850 a group of seven families decided to settle Diamond Springs, not only to take advantage of its rich placer mining opportunities, but for the area’s great potential as farmland.

Some early histories of El Dorado County state that the towns name originated from the crystal-clear springs located nearby. Other accounts attribute the name to the 25-pound nugget found in a local mine. This nugget was the largest recorded piece of gold found in El Dorado County.

Diamond Springs reached its peak in 1851. At that time clapboard homes had sprung up to support the growing population of 1,500, and Main Street was lined with mercantile stores, hotels, saloons, butchers, bakers, and blacksmiths.

Just a few years later in 1856 fire, which was all to common in early gold rush towns, destroyed all but two brick buildings in Diamond Springs. One, the Wells Fargo Express Office still exists today. We will point it out when we drive through town.

After another fire in 1859 the resilient residents rebuilt again, this time in brick. Today most of this town’s industry revolves around lumber, agriculture and limestone mining.

Ads for riders read: Wanted “Young, skinny, wiry fellows anxious for adventure, not over 18. Must be expert riders and willing to risk death daily. Wages $25 per day. Orphans preferred.”

The Pony Express lasted eighteen months from April 1860 to November 1861, when the transcontinental telegraph made the service obsolete.

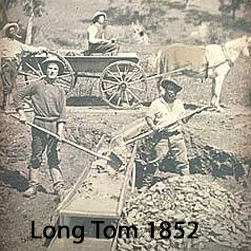

During the first few years after gold was discovered, miners simply panned for gold in California’s rivers using pie shaped plates. This was called placer mining. Later they expanded to sluice boxes and long Toms. In 1853 hydraulic mining, the act of directing water through a high-pressure hose against gold-bearing gravel beds, became popular. Due in part to the sever erosion this method caused, hydraulic mining was outlawed in 1884. Dredging, which was a continuous line of steel buckets that sifted through the dirt at the bottom of rivers, became popular in the late 1890s.

As placer mining panned out, or basically drew to a close, miners developed another gold recovery method, lode or hard-rock mining. This process involved extracting gold directly from the rock, typically quartz rock. By 1851 quartz hard-rock mining had become a major industry in California’s Mother Lode and would eventually become the largest source of gold production in California’s gold country.

The Mother Lode, which begins in Coloma and runs south about 120 miles to the town of Mariposa, is a large system of gold-quartz veins. They branch out, in no particular fashion, along this corridor and constitute the best-known mining districts in California.

The most productive portion of the Mother Lode is the 1-mile segment between Plymouth and Jackson in Amador County. We will be driving through these towns later on our tour.

But before we get to these larger towns, we must drive through some of the smaller lesser known ones, starting with Logtown, which in 1850 boasted 420 inhabitants, mostly miners.

In a “Letter from Logtown,” published that same year, the community was described as “Quite a village. There are not less than 20 stores, two blacksmith shops, two taverns, shoemakers, bakers, carpenters, and one gambling house. Preaching is done here nearly every Sabbath, and always in good attendance.”

Between 1890 and 1894 the most productive hard-rock lode mine in Logtown was the Starlight Mine. This 500-foot mine shaft connected to a three-foot vein of gold-bearing quarts. Getting the ore out of the mine was a laborious process.

Prospectors used pickaxes to dig deep into the ground to get to the ore. Once the ore was removed it was transported in large pieces by wheeled carts. These heavy carts were rolled along a track to the stamp mill. The stamp mill operated as a rock crushing machine. It usually contained sets of 5 stamps, heavy steel rod shafts that alternated in an up and down motion crushing the ore and separating the gold. A 10-stamp mill contained 2 sets of 5 stamps, a 20-stamp mill 4 sets of 5 and so on. The larger the mill the larger the gold mining operation.

What remains now of Logtown is little more than what was there before the gold rush hit, grassy hills, rustic barns, and groves of oak trees.

The next chapter in John Doble’s gold rush adventure was his journey from San Francisco to the mines. John left San Francisco January 6, 1852 and traveled overnight by steamboat up the San Joaquin River to Stockton. Here is a paraphrased excerpt from John's diary recalling his 40 mile journey from Stockton to Latimers Gulch.

"I put up at Galt House in Stockton a flourishing town on the riverbank, but it is built so low I had much difficulty along the streets which were hub deep in mud.”

“The next day I walked 6 miles and put up for the night in Semmins where several wagons had stopped. I tried to make a bargain with them to haul me as the walk had tired me very much, but their prices were more than I wished to give.”

“The next morning I paid my bill for supper, breakfast, and bed, $1.75. I put out and walked 15 miles to the next roadhouse. Too tired to walk any more, I put my carpet sack and blankets in the back of a wagon. I will pay for my ride. The wagons stopped for the night at the Tremont house in a narrow valley on a beautiful mountain stream about 35 miles from Stockton.”

“I continued with the wagons to Double Springs where we parted. They are going on to Camp Seco on the Mokelumne and I am going to Latimers on the Calaveras. I paid them $1.37 for the ride. Passed over several deep canyons on my way to Latimers and arrived at 5 o’clock. Met Major and Doc they told me about work some 2 miles from here. I will check that out tomorrow.”

As we continue with our driving tour, the highway will wind alongside the Consumnes River, which will come into view on your left.

The Consumnes begins on a western slope of the Sierra Nevada and flows about 50 miles emptying into the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta. We will be following this river as we leave Placer County and enter Amador County.

Up ahead notice the sign for Nashville, it was originally named Quarzville after the quartz vein mined here in 1851. This tiny town along the north fork of the Consumnes River was renamed Nashville after the town in Tennessee when the post office was established in 1852. The hard-rock mines in this area were the first to introduce the quartz crushing method that used an arrastre.

An arrastre is a mill for grinding gold ore that was introduced by Mexican miners in 1849. Its simplest form is two or more flat-bottomed stones placed in a circular pit paved with more flat stones. This system was connected to a center post by a long arm. With a horse, mule or human providing the power at the other end of the arm, the stones were dragged slowly around in a circle, crushing the ore, and separating it from the gold.

Continue straight on California Highway 49 and cross the North Fork of the Cosumnes River while we tell you more about John Doble, a hearty soul with golden dreams.

“The next day I bought tools necessary for work. An iron shovel $2.00, small pick with handle $2.50 and tin pan for washing gold $1.50. Now ready I set out sinking a hole on a small flat below Latimers. I worked all day but could get nothing but small specks which I did not save. I worked very slow as I knew nothing about it and the ground was hard to dig being full of stones. By night I got a hole about 3 feet square and 4 feet deep and was very tired.”

“The next day the 11th, Major and I went out and sunk the hole to the ledge but found nothing more. The bedrock is found almost everywhere among the hills at a few feet below the surface and that is where most of the gulch gold is found. We quit the hole and went down to the river and washed several pans of dirt but got nothing more than small specks. The river here runs through a narrow canyon. On each side the rocks rise almost perpendicular by several hundred feet. We soon returned to the boarding house in Latimers tired of prospecting.”

"Latimer keeps a store and boarding house and being on the road, a tavern. This day, Sunday, it was crowded with customers as few work but do trade at the store. We ate dinner at the tavern and met Doc and Holbrook who were just returning from work. They reported good prospects over on the divide between the North Fork of the Calaveras and the Mokelumne River. On their report we will set out tomorrow to Angiers near their prospect.”

The next gold rush town we visit along Highway 49 is Plymouth, California. The first mining camp here was established in 1852, but it would be Alvinza Haward's arrival in 1871 that would put Plymouth on the map.

Almost overnight a general store, hotel, blacksmith, post office and several saloons had opened on main street to meet the growing needs of the miners that worked the Aden-Simpson mine. By 1883 the large number of hard-rock mines worked here merged into the Plymouth Consolidated Mine Company, which produced over $13 million in gold before selling out to Argonaut Mining Company in 1925 for $75,000.

Besides being the location of the Amador County Fair which takes place every year on the last weekend of July, today Plymouth is known as the “gateway to the Shenandoah Valley,” which boasts over 20 wineries as well as the Amador Flower Farm. We will visit the Shenandoah Valley later on this driving tour.

At the roundabout ahead we will leave Highway 49 and take the first right onto Main Street in Plymouth. If you would like to explore this town on foot you may find a map in our Companion Brochure or use the map above. Otherwise just keep driving along Main, while we point out a few buildings.

On your right as you exit the roundabout is the Plymouth House Bed and Breakfast. This Victorian house was built in 1885.

To you left, the dark grey building is Prospect Cellars. Located in the original Plymouth post office building this wine room which is open Thursday through Sunday starting at noon, is part wine tasting room, eatery, and visitors center.

When you arrive at the roundabout, turn right and take the second right onto Shenandoah Road. Follow Shenandoah Road and veer to your left along the highway.

As you enjoy this back county road lined with family-owned vineyards we will tell you the story of another kind of gold found in the Mother Lode.Not all fortune seekers who flocked to California during the Gold Rush made their wealth in gold dust. Many who were unable to strike it rich in the mines, stuck around to become part of California’s budding wine industry.

Today Amador County is home to over 40 wineries and Shenandoah Valley contains over half of them.

As most of the wineries along Shenandoah Road require reservations to visit, we will call out a few that do not. But feel free to stop in at any winery that strikes your interest. If they have an open sign on the highway, you never know, they just my wave any reservation requirement.

The California Shenandoah Valley American Viticultural Area, or AVA, was established in 1983. AVA’s distinguish different grape-growing regions in the United States, categorizing them by specific geography, soil, climate or other features. Using an AVA designation on a wine label allows vintners to describe the origin of their wines more accurately to consumers.

At the time of this writing, there are 260 AVA’s in the United States with California having the most at 142.

Shenandoah Valley’s AVA is distinguished by its location, age of vines, and soil. Of all the AVA’s in the vicinity, the Shenandoah Valley is positioned in the least elevated and warmest portion of the Sierra Foothills. The average elevation of 1500 feet provides just the right amount of heat and optimal conditions to produce top-quality wine grapes especially Zinfandel, Sangiovese, and Barbera.

The soil here is largely made up of decomposed granite sand and clay. Well drained and infertile, it is excellent for growing wine grapes.

The combination of Shenandoah Valley's location, its excellent soil, and warm dry climate produces wines that are rich and complex.

Fiddletown was settled in 1849 by gold miners from Missouri. Though the origin of the name is uncertain, some say that the name came from the Missouri miners who were always playing their fiddles when not at work in the mines. The name, which was an embarrassment to some residents, was changed to Oleta in 1878 and then due to popular demand restored once more to Fiddletown in 1932.

By 1854 Fiddletown's populace had grown to around 2,000. Most were American, but by 1878 Fiddletown's Chinese population was the second largest in California, only San Francisco's was larger.

Today Fiddletown's rustic western style downtown is only 1/4 mile long. While we drive through the town, we will point out some of the remaining historic buildings including the Chew Kee herb store, which is now a museum, the Chinese Gambling Hall, and Foo Kee General Store.

Fiddletown claims it has the world's largest fiddle. The 15 foot long fiddle is mounted on the roof of the community center downtown. If we're not mistaken, we believe Sydney Australia holds the record of the worlds largest fiddle at 60 feet. But let's just keep that to ourselves.

When you come to the end of Ostrom Road, turn left onto Jibboom Street in the direction of Highway 88.

On your left, the cream colored home with the peaked roof on Jibboom is the Hiram Farnham house. Built in 1855 on the outskirts of Fiddletown, this home overlooked the Farnham steam powered sawmill. In its heyday in 1857 this sawmill produced over 8,000 board feet of lumber per day.

Turn right onto Tyler Street and then right onto Fiddletown Road. You are now in downtown Fiddletown.

Down the road on your left are two brick buildings both constructed in 1850. The first, with a double-panel white door and teal trim, is Foo Kee General Store.

We are now headed back toward Plymouth on Fiddletown Road. It is approximately 6 miles to our next turn off. While you drive along Fiddletown Road, we have another store to tell.

Prior to1848, almost everyone living on the East Coast, in the Midwest or in the South thought that California was a remote and nearly worthless wilderness. But that all changed when Gold Fever took the world by storm after James Marshall discovered a few flakes of gold near John Sutter’s sawmill in Coloma, California on January 24, 1848. Initially Marshall and Sutter tried to keep this discovery a secret. But that was not to last.

Businessman and journalist Sam Brannan had a brilliant idea, and he would make a fortune off it. Brannan was privy to the discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill, and he cleverly thought to buy up all the mining supplies in the San Francisco area. Then holding a bottle, allegedly containing gold flakes, he walked up and down Montgomery Street in San Francisco shouting: “Gold! Gold! Gold from the American River.” His idea worked like a charm. As soon as he announced, “there was gold in them thar hills,” men flocked to his store to buy everything they needed to make their fortune panning for gold.

In January 1848 the population of what would soon become the state of California was about 160,000, the vast majority Native American. Six months later the word was out, and 4,000 miners had already arrived in the Sierra foothills.

By the end of 1849, 80,000 “forty-niners” as they were called, were working the California goldfields. By 1855 that number had grown to 300,000. Historians call this the largest mass migration in U.S. history.

Besides Americans, these fortune seekers came from Mexico, Chile, China, Japan, Europe, and Australia. Most had no actual plan or knowledge on how to mine for gold, but they were stricken with Gold Fever, and knew California was where they would make their fortune.

Leaving their homes and families behind these men, and some women, embarked on a very difficult journey. No planes, trains, or automobiles. No roads for that matter. Instead, it was a long hike, wagon train, mule ride or ocean voyage.

From the east, prospectors took a five to eight-month voyage around Cape Horn. Others sailed to Panama and hiked across the Isthmus to catch a ship on the Pacific Ocean side, then sail on to San Francisco. Along the way they faced starvation, shipwrecks, cholera, and numerous other challenges. Yet golden dreams had seized their hearts, minds, and imaginations, so it was California or Bust for these hearty souls.

Which brings us back to our friend, John Doble. Our story takes up at Latimers Gulch with his diary entry of January 14, 1852.

"This morning we went to work making the Tom, which is a trough the length of the plank and width of one plank and about 6 inches deep with a sheet of iron riddle at one end through which the fine gravel water and gold falls into a box beneath. The gold being the heaviest sinks to the bottom and the gravel and dirt is washed away. Being a novice we are very tired from this work."

"On Friday I made my first gold, .20 cents. On Saturday I made one dollar. Others nearby made $20 so I am not discouraged."

"On Sunday Major and I went to Alabama Gulch which lies about 1/2 mile down a falls from Angiers. The falls frequently wash 40 feet over smooth granite rocks. We went down over the falls, sometimes sliding a distance. At the river I washed 5 pans and got .20 cents which brings me to $1.40."

"We returned by the trail climbing back up the mountain. When we arrived at Algiers the store was crowded with a good many miners tolerable tight or in other words 1/2 drunk. They sang sailor songs and played the fiddle all night."

"After two weeks working near Algiers I could not make my board which was $10 a week and was forced to leave the boarding house."

Up ahead you will come to the end of Fiddletown Road, turn left and continue back in the direction of Plymouth. When you get to the roundabout, turn right and take the 3rd exit onto California Highway 49 South. We are on our way to Drytown.

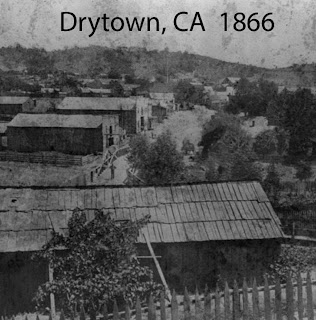

This gold rush town was settled in 1848. Far from "dry” like towns were during the Prohibition, Drytown contained 26 saloons. The name was derived from the creek nearby that ran dry during the summer. By 1849 a few hundred miners lived and worked this area.

Miner John Doble visited Drytown frequently to pan Dry Creek or another nearby gulch. On July 18th 1852 he wrote “Started by sun up this morning for Drytown with Stewart who worked there before. Stopped at Stewart’s friends and got some dinner. As we came down the creek, we passed many Chinese at work. The town consists of about 200 houses and is on the south side of the creek. We went down two more miles to New York Gulch. Stewart had worked here before and wanted me to take a claim which was jumpable, but I did not want to do it as there might be hard feelings about it and I don’t believe in jumping claims nohow.”

How did miners originally stake claims during the gold rush? It was fairly simple actually. First locate an area on public land that was not currently claimed. Prospect it and find at least one piece of gold, then place a rock monument in each corner and label the claim with a name and it is yours. To keep that claim miners had to work at least one day out of every 5 at the site, otherwise the claim was jumpable. With the population ever growing along the Mother Lode, claim jumping was common.

In 1857 Drytown’s population had peaked at 10,000, yet almost as fast as it had begun, gold mining began to dry out in Drytown. By 1858 most of the inhabitants had packed up and moved onto their next claim.

Today you will find a handful of antique and gift shops.

This country road takes us through New Chicago a town that sprung up during the 1850s to support the Fremont Gover hard-rock mine. The remains of the Fremont Gover headframe will be visible in the distance ahead on your right shortly. Headframes were used to hoist materials in and out of the mine shaft.

During the gold rush, New Chicago was a medium sized town with 20 houses, a grocery store and hotel. Today you will find a few large country estates.

Turn right ahead onto Bunker Hill Road toward the remains of the headframe of the Fremont Gover Mine. With a total production of about $5 million this mine was worked intermittently until 1940.

Ahead you will drive by the remains of the Fremont Gover mine headframe. At the "Y" in the road stay to the right to continue along Bunker Hill Road.

Next on your left surrounded by a grove of trees is the headframe of Treasure Mine. This mine was founded in 1867 and closed in 1922 after producing $1 million in gold. The 1,600 foot level of Treasure Mine connects to the Bunker Hill Mine, which we will pass shortly.

The Bunker Hill Mine has a tragic story attached to it. In 1999 Jack Sackrider killed his girlfriend Tina Foligno and threw her body into the shaft of the Bunker Hill Mine. She was found at the 250-foot level and Jack is now serving time in prison.

You may use the map above or access the companion brochure for a walking tour of Amador City. From this parking lot it is a short walk into town.

Continue along the highway a few more miles and you arrive at the outskirts of Sutter Creek. Watch for the two-story brick Hanford Building and then turn right. This is the main street of Sutter Creek. The three pictures below are of Sutter Creek. They date from the 1860's to 1900's.

Today Sutter Creek's charming main street is lined with typical western style buildings, most rebuilt in stone or concrete after the fire of 1888.

Just past the foundry banner there is a small parking area. Park here to visit the outdoor museum which describes the history of Samuel Knight's enterprise.

Established in 1873 by Samuel Knight this foundry, which is recognized as a National Historic Mechanical Engineering Landmark, is America’s last water-powered foundry and machine shop. The facility includes unique historic equipment and machinery in its original context of the gold rush era. Essential to the operation of area mines, this foundry manufactured stamp mills, hoist works, pumps, ore cars, dredger buckets, rock crushers, and more.

Samuel Knight came to California from Maine in 1863. In 1875 Knight developed a cast iron high-pressure water turbine wheel. These water wheels eventually became the prevalent mover of gold country industrial equipment. Inside Knights Foundry a 42-inch wheel drives the main line, with smaller water motors powering the other machines.

After 1883 the Knight wheel experienced stiff competition from the Pelton Water Wheel. Though the Pelton wheel proved to be more efficient, by the 1890s more than 300 Knight Wheels had been produced and were in use across the Western United States. Knight also created several other types of mining equipment crediting this foundry with a total of eight patents for machines designed in his shop.

The City of Sutter Creek now owns the foundry and is in the process of preserving the building and its contents. It is open the second Saturday of the month for self-guided tours.

This park features gold mining artifacts from the Argonaut, Lincoln Mine and the Knight Foundry as well as informational plaques with historic photos.

This was also the site of the worst mining disaster in the Mother Lode. In August 1922 a fire broke out deep in the Argonaut mine. Rescue workers used the Kennedy Mine down the road to stage a rescue. They drilled from the Kennedy Mine into the Argonaut and entered equipped with oxygen tanks and a canary.

Buildings in this old part of town were constructed out of brick after the fire of 1862. They have been well maintained and today house a number of offices, restaurants, specialty stores, and bars.

The Main Event Bar ahead on your right was the county jail in 1862.

On your left, Rosebuds, was the location of Jackson’s founder, Louis Tellier’s saloon and the towns Hanging Tree where ten were hung from its branches.

Across the street, Crucible Jewelers with the red awning, was the birth place of wine industry titan, Ernest Gallo in 1909.

Then turn right into the parking garage in the red brick Jackson Civic Center building before you get to the end of this block.

It is a short walk from this location into historic downtown Jackson. You will find a map of this area in our companion brochure.

We hope that you have enjoyed your driving tour from Placerville to Jackson and all of our stops in-between.

This is one of four companion tours of the California Gold Rush Back Roads and Highway 49 from Auburn to Jamestown. If you are interested in the next segment, we end our tour in the parking lot where we begin our next driving tour, Jackson to San Andreas.

All Pictures by L. A. Momboisse unless listed below:

Placerville 1866 - Library of Congress

Placerville From Cary House 1866 - Library of Congress

Placerville 1888 - Library of Congress

Old Town Placerville - Visit El Dorado - Visit El Dorado An Afternoon in Placerville

3 pictures of Diamond Springs Hotel - Website

Ad for Wells Fargo & Co - Wikipedia

Henry Wells and William Fargo - Wikipedia

1860's Wells Fargo Stagecoach - Wikimedia Commons

William Russell, Alexander Majors and William Waddell - Historic Marker Database

Pony Express Route - Legends of America

Placer Miners with their tools - Courtesy Bancroft Library

Crystalline gold specimen from the California Mother Lode (5.3 x 2.7 x 2.4 cm) - Wikipedia

Gold Bearing Quartz Vein - Photo by Ron Wolf / Logtown Story

California Gold Rush - Library of Congress

Alvinza Hayward - Wikipedia

Old Vine Amador County - Amador County Wines

Aerial of Amador Flower Farm - Courtesy of Amador Flower Farm

Sam Brannon - Wikipedia

49ers in the Gold Fields - A Day in the Life of A Miner

Getting There is Half the Fun Newspaper Ad - A Day in the Life of A Miner

Long Tom 1852 - California State Library

Drytown 1866 - Wikipedia

Miner with Equipment - Wikipedia

Three period black and white pictures of Sutter Creek - Sutter Creek Jewel of the Motherload

Worker's in Knight's Foundry - Knight's Foundry Website

.jpg)

.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment